Notes: A mechanism for emergence of complex patterns in continuous CA's

I) Motivation

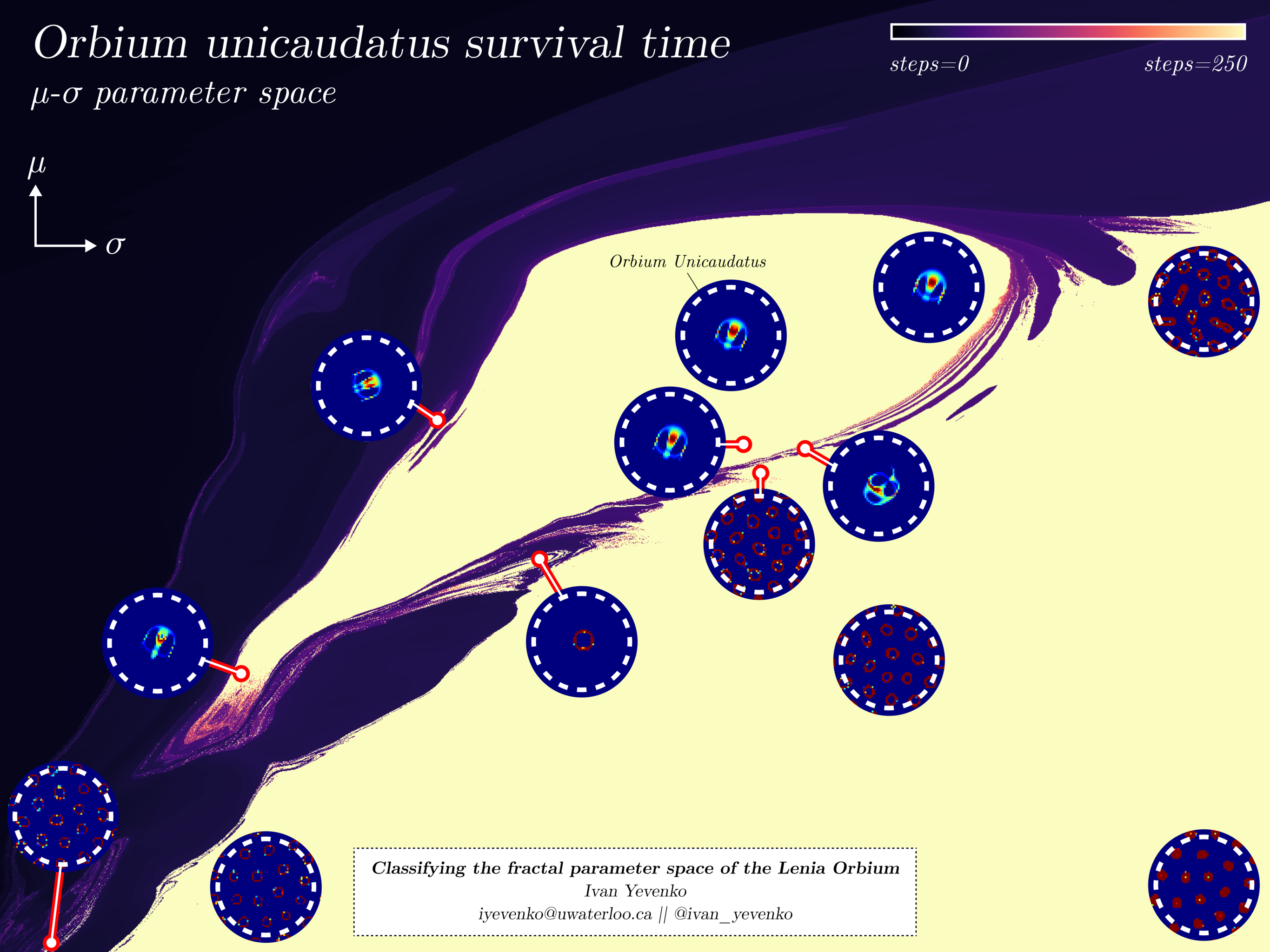

In my first paper, I discovered that varying the simulation parameters of the Lenia CA had an extremely complex effect on the resulting patterns. In particular, the survival time of the creatures (i.e. halting time of the simulation) was fractal with respect to the parameters. I also found that this fractal space was clearly divided into 3 regions corresponding to the zero attractor, a soliton attractor and a chaotic attractor.

Visualizing this space was very insightful, since I could now explain the complexity of the patterns as indicative of some kind of intrinsic irreducibility of the system. This is intuitive because the governing equation of Lenia is far from reducible. In short, irreducible dynamics are bound to produce complex patterns.

It's easy to stop here and say "clearly these patterns are too complex to understand analytically" and conclude that the best way to look for new patterns is still an evolutionary search. However, I was convinced that there is a deeper reason for the emergence of these patterns, and the biggest clue was the attractor towards a purely translating pattern.

In my poster, you can see that the Orbium Unicaudatus pattern discovered by Bert Chan is at the center of a basin of attraction for translating patterns. In fact, the patterns near it in the parameter space are the most stable, meaning they deviate the least from a purely translating pattern. Clearly somewhere near the center of the basin of attraction is an analytical solution corresponding to linear translation over time.

II) Theoretical Background

Below I'll explain the mathematical framework I'm using, but feel free to skip and come back later. Continuous CA's are typically defined as a scalar field \( \mathbf{A}(\vec{r}, t): \mathbb{R}^2 \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) that evolves according to some dynamics:

$$ \partial_t \mathbf{A} = f[\mathbf{A}] $$

Where \( f[\mathbf{A}] \) is some operator typically involving a spatial 2D convolution. However, since the CA needs to run on a computer, \(\mathbf{A}\) is necessarily discretized in space and time to approximate the continuous field. For example, the Lenia CA on an \(H \times W\) grid is defined as:

$$ \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t+\Delta t) = \left[ \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) + \Delta t\, G(\mathbf{K}(\vec{r}) * \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)) \right]_0^1 \,, \quad t,\Delta t \in \mathbb{R}^+ ,\, \vec{r} \in [0,H]\times[0,W]$$

Where \(G: \mathbb{R} \to [-1,1]\) is the growth function, \(\mathbf{K}(\vec{r}): \mathbb{R}^2 \to [0,1]\) is a radially symmetric kernel function and \(\left[ \cdot \right]_0^1\) is a clipping function that ensures the field remains in the range \([0,1]\). This equation, while simple to implement in code, is practically impossible to work with analytically. For this reason, Asymptotic Lenia was developed by Kawaguchi et al., which transforms the equation to a single continuous PDE while maintaining all the qualitatively interesting behavior of Lenia (video). Most importantly, translating and rotating patterns are still attractors of the system. See for yourself in my web simulator! The equation for Asymptotic Lenia is:

$$ \partial_t \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = T(\mathbf{K}(\vec{r}) * \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)) - \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)$$

Where \(T: \mathbb{R} \to [0,1]\) is just \((G+1)/2\). For my analysis, the growth function I use is the piecewise constant function:

$$ G(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \mu - \sigma \leq x \leq \mu + \sigma \\ -1 & otherwise \end{cases}\,, \quad \mu,\sigma \in [0,1] $$

Where \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are parameters that control the growth rate of the field, carried over from the original Lenia rules. In other words, the dynamics at a particular point in \(\mathbf{A}\) are either an exponential decay or an exponential growth, depending on the update field \(\mathbf{U}(\vec{r},t) = \mathbf{K}(\vec{r}) * \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)\).

$$ \partial_t \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = \begin{cases} 1 - \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) & \mu - \sigma \leq \mathbf{U}(\vec{r},t) \leq \mu + \sigma \\ -\mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) & otherwise \end{cases} $$

One thing I noticed early on was that the dynamics of the field had a very similar form to gradient ascent. In fact, I found that with my choice of growth function, I could rewrite the dynamics as:

$$ \partial_t \mathbf{A} = \nabla \left [ \mathbf{A}\, T(\mathbf{K}*\mathbf{A}) - \tfrac{1}{2}\mathbf{A}^2 \right ] $$

Since \(T^{\prime} \approx 0\) due to its piecewise constant nature (I argue that it's fair to ignore the infinities since they do not exist in numerical simulations). So what does this mean? Well, it means that the system is maximizing some value, which is the integral over space of the quantity inside the gradient, which can be thought of as the Lagrangian \(\mathcal{L}[\mathbf{A}]\) of the system. But if we have a Lagrangian, then we must be able to define an action \(S[\mathbf{A}]\) and solve the Euler-Lagrange equation! So if we define \(S\) as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} S[\mathbf{A}] &= \int_0^{t} \mathcal{L}[A] dt \\ &= \int_0^{t} \int_{\mathbb{R}^2} \mathbf{A}\, T(\mathbf{K}*\mathbf{A}) - \tfrac{1}{2}\mathbf{A}^2 d\vec{r} dt \end{align*} $$

Then, since \(\mathcal{L}\) depends only on \(\mathbf{A}\), the Euler-Lagrange equation is simply:

$$ \begin{align*} \delta S = 0 \iff 0 &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{A}} \\ &= T(\mathbf{K}(\vec{r}) * \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)) - \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) \\ &= \partial_t \mathbf{A} \end{align*} $$

This tells us that only steady-state solutions of the form \( \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},0) = T(\mathbf{K}(\vec{r}) * \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},0)) \) extremize \(S\). That also means that translating and rotating patterns do NOT extremize \(S\). But look at the graph of the Lagrangian for a soliton solution:

Clearly the Lagrangian converges to a steady state value without ever reaching a stationary point. This means that the pattern on its own is not a local extremum of the action, but moving along the gradient of the action doesn't change it. Another way to think about it is the Lagrangian has an extra degree of freedom at this point in the optimization space, causing the optimization process (remember the PDE is equivalent to maximizing the Lagrangian) to get stuck on this translating trajectory.

There's actually a very simple mathematical reason for this! The Lagrangian is invariant under translations (and rotations) of the field. This is why a pattern that translates over time corresponds to a flat line on the Lagrangian vs time graph, despite not being a local extremum. However, knowing that translating patterns leave the action unchanged doesn't imply that these patterns satisfy the dynamics of the system. To understand why these emerge, it will be more useful to look at symmetries of the differential equation, rather than Lagrangian. This is well motivated, since there exists a formal correspondence between symmetries of a Lagrangian and symmetries of the differential equation it governs.

Fortunately, the tools of Lie theory — namely the infinitesimal generator of a symmetry and the exponential map — provide a beautiful framework for dealing with symmetries of differential equations. First, I'm going to use the known fact that the infinitesimal generator for a translation by some vector \(\vec{v}\) is \(\vec{v} \cdot \nabla\), where \(\nabla\) is the gradient operator. This can be written as:

$$\exp (\vec{v} \cdot \nabla ) \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = \mathbf{A}(\vec{r}+\vec{v},t)$$

But notice that this allows us to write a translating solution as:

$$ \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = \exp (t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},0)$$

Now we can plug this ansatz into the Asymptotic Lenia PDE. For simplicity, I will use \(\mathbf{A}_0\) to mean \(\mathbf{A}(\vec{r},0)\). I will also make use of the fact that the right hand side of the PDE is equivariant under translations.

$$ \begin{align*} \partial_t \exp (t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{A}_0 &= T(\mathbf{K} * \exp (t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{A}_0) - \exp (t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{A}_0 \\ \exp (t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \left[\vec{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{A}_0\right] &= \exp(t \vec{v} \cdot \nabla) \left [ T(\mathbf{K} * \mathbf{A}_0) - \mathbf{A}_0 \right ] \\ \vec{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{A}_0 &= T(\mathbf{K} * \mathbf{A}_0) - \mathbf{A}_0 \end{align*} $$

Therefore, as long as the initial condition \(\mathbf{A}_0\) satisfies the above equation, it will linearly translate indefinitely. This is exactly what we were looking for! To summarize, we started with a symmetry of the lagrangian (equivariance of the RHS of the PDE), and showed that a very specific form of solution to the PDE must exist which does not extremize the action, but leaves the lagrangian unchanged. It turns out that this is a very general result that applies to many other symmetries and differential equations. In the next section, I attempt to rigorously prove this result for in as general of a case as possible.

III) Theoretical Results

Here's my work-in-progress proof. Suppose you have a PDE of the form:

$$ \begin{equation} \partial_t \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = f[\mathbf{A}](\vec{r},t) - \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) \label{pde} \end{equation} $$

Where \(\mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t)\) is a real-valued scalar field \(\mathbf{A}: \mathbb{R}^2 \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) and \(f\) is an operator operating on the entire field, allowing for non-local interactions (e.g. a convolution). If \(f\) is equivariant under one-parameter transformations \(\gamma(s), s \in \mathbb{R}\) belonging to the abelian Lie group \(\mathcal{G}\), then \(\mathcal{G}\) is said to be a symmetry group of the PDE if:

$$ \begin{align*} \partial_t \left[\gamma(s) \cdot A(\vec{r},t)\right] &= f\left[\gamma(s) \cdot A\right](\vec{r},t) - \gamma(s) \cdot A(\vec{r},t) \\ &= \gamma(s) \cdot f\left[A\right](\vec{r},t) - \gamma(s) \cdot A(\vec{r},t) \end{align*} $$

This is a consequence of Theorem 2.27 of Applications of Lie Groups to Differential Equations. Now, suppose \(M\) is an element of the Lie algebra corresponding to \(\mathcal{G}\), representing an infinitesimal transformation of the field \(\mathbf{A}\). Motivated by this, I consider the ansatz \(\mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})\), where I define the initial condition \(\mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) = \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},0)\) as a scalar field over \(\mathbb{R}^2\). Then, the invariance condition becomes:

$$ \begin{align} \partial_t \left[e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})\right] &= e^{t M} f[\mathbf{A}_0](\vec{r}) - e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) \nonumber \\ M e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) &= e^{t M} f[\mathbf{A}_0](\vec{r}) - e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) \nonumber \\ e^{t M} M \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) &= e^{t M} [f[\mathbf{A}_0](\vec{r}) - \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})] \nonumber \\ M \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) &= f[\mathbf{A}_0](\vec{r}) - \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) \label{stationary_cond} \end{align} $$

Therefore, as long as there exists a stationary solution \(\mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})\) that satisfies \(\eqref{stationary_cond}\), \(\mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = e^{t M} \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})\) will be a solution of \(\eqref{pde}\). By taking \(M=\vec{v} \cdot \nabla, \vec{v} \in \mathbb{R}^2\), and \(M=\omega \vec{r} \times \nabla, \omega \in \mathbb{R}\), which are the generators of translations and rotations respectively, I have successfully predicted the existence of translating and rotating solutions of \(\eqref{pde}\).

Furthermore, it's possible to show that the solutions corresponding to symmetries are also attractors of the system. However, I have not yet figured out how to prove this rigorously. Finally, to fully explain the emergence of complex patterns, consider continuously parameterizing \(f\) with some parameter \(\mu\). Then, if the parameters \( \mu_1, \mu_2 \in \mathbb{R}\), are \(\varepsilon\)-close (i.e. \(|\mu_1 - \mu_2| \le \varepsilon\)) such that \(\eqref{stationary_cond}\) has a solution under \(f_{\mu_1}\) but not under \(f_{\mu_2}\), AND \(f_{\mu_2}\) does not evolve to a steady state, then the system will exhibit complex behavior. Put another way, if there exists a set in parameter space \([\mu_1 - \varepsilon, \mu_1 + \varepsilon] \setminus \{\mu_1\}\) that neither goes to a steady state, nor obeys the symmetry condition, then the system will exhibit complex behavior in that region.

Now recognize that this region is precisely the fractal region I discovered in my first paper! Go back and look at the poster, and imagine that somewhere in the middle of what I called Orbium Island, there is a parameter tuple \((\mu_1, \sigma_1)\) that corresponds to a pure translation. In a fractally-bounded neighborhood around this point, the patterns are either numerically indistinguishable from pure translation, periodic, or chaotic. We've now successfully connected a purely theoretical result to the super complex patterns that seemed totally unapproachable from an analytic perspective.

IV) Implications

There are many practical implications of the theoretical results. For one, knowing what kinds of behaviors are possible and why they emerge makes it much easier to look for novel patterns. I have conjectured that all known patterns in continuous CA's of the form in \(\eqref{pde}\) either evolve to a steady state (extremizing the action), or almost obey a symmetry condition. So all we need to look for are stationary solutions to \(\eqref{stationary_cond}\) and then explore the surrounding region in parameter space. What's great about that equation, is that we only need to find an initial condition over space, and no time evolution is required. So one way to look for translating patterns in Asymptotic Lenia might be:

- Choose a random initial field from some fixed distribution

- Minimize with gradient descent: \( L(\mathbf{A}_0) = \left( \vec{v} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{A}_0 - T(\mathbf{K} * \mathbf{A}_0) + \mathbf{A}_0 \right)^2 \) for some \(\vec{v} \in \mathbb{R}^2\)

- Choose two parameters from \( (\mu,\sigma,\beta_i,R,T) \) and plot the survival time for the pattern \(\mathbf{A_0}\) as you sweep over a range of these values.

- Manually classify different behaviors in the parameter space.

I think pattern discovery is not the most exciting application of this work though. Due to the general nature of the results, I have made a statement about a very broad class of differential equations. I have determined the following conditions to be sufficient for the emergence of complex behavior:

- We have a scalar field \( \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t): \mathbb{R}^2 \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) that evolves according to \( \partial_t \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) = f[\mathbf{A}](\vec{r},t) - \mathbf{A}(\vec{r},t) \) where \( f \) is an operator that depends only on the value of the field itself and possibly \( \vec{r} \).

- \(f\) is equivariant under some one-parameter transformation \(\gamma(s) \in \mathcal{G}\) where \(\mathcal{G}\) is an abelian Lie group. Also, \(f[\mathbf{0}]=\mathbf{0}\) (there is likely a more precise condition for \(f\) to make the symmetry-obeying solutions attractors).

- There exists an initial condition \(\mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r})\) that satisfies \( M \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) = f[\mathbf{A}_0](\vec{r}) - \mathbf{A}_0(\vec{r}) \) where \(M\) is an element of the Lie algebra of \(\mathcal{G}\).

- Continuous parameterizations \(f_{\mu}\) can be shown to break the symmetry without devolving into steady state solutions.

Designing systems with emergent complexity is a super exciting prospect, but I have yet to experimentally validate the results. I'm currently studying the symmetries that arise in quantum field theory (QFT) to get some inspiration for the kinds of symmetries I can design into my system. The goal is really to be able to design a novel artificial life system that exhibits different kinds of copmlex behavior from what we're used to seeing.

That's it for now! More updates coming soon!